From Chapter 3, The Empress, Meditations on the Tarot.

From Chapter 3, The Empress, Meditations on the Tarot.

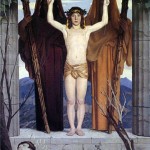

But it so happens that in human consciousness one separates the inseparable – in forgetting the unity. One takes a branch of the tree and cultivates it as if exists without the trunk. The branch can have a long life, but it degenerates. It is thus that in forgetting gnosis and mysticism, magic has been taken separately which, being a branch separated from its trunk, ceased to be sacred magic and became arbitrary or personal magic. This latter mechanized to a certain degree and became what one understands as ceremonial magic which flourished from the time of the Renaissance until the seventeenth century. It was par excellence the magic of the humanists, ie., it was no longer divine magic, but human magic. It no longer served God, but man. Its ideal became the power of man over visible and invisible Nature. Later invisible Nature was also forgotten. Visible Nature was concentrated upon alone, with the aim of subjugating it to the human will. It is in this way that technological and industrial science originated. It is the continuation of the ceremonial magic of the humanists, stripped of its occult element, just as the former is a continuation of sacred magic, but deprived of its gnostic and magical element.

More might be said here – for example, the degeneration of the current cycle or branch of mankind in comparison to the past, the decay of religious and cultural forms in recent memory (eg., Protestantism, etc.), as well as noting the imagery of a branch broken from the tree of life. Man believes he can pluck the fruit, and retain it. This is the inner meaning of decline. What would the true man oppose to this? He then quotes Papus (also citing Eliphas Levi):

Ceremonial magic is an operation by which man seeks, through the play of natural forces, to compel the invisible powers of diverse orders to act according to what he requires of them. To this end he seizes them, he surprises them, as it were, in projecting, through the effect of correspondences which suppose the unity of Creation, forces of which he himself is not master, but to which he can open extraordinary outlets…ceremonial magic is of an order absolutely identical to our industrial science. Our power is almost nothing alongside that of steam, electricity, and of dynamite; but in opposing them by appropriate combinations to natural forces as powerful as themselves, we concentrate them, we accumulate them, we compel the to transport or to smash weights which would annihilate us. Traite elementaire de science occulte, Paris, 1888 pp 425-426.

This is why salvation will not automatically spring from the research of the nuclear physicists in Bern (or anywhere else), despite our fond dreams and hopes, and despite the value of science. The above observation is virtually identical to something which lay at the heart of the work of George MacDonald, the genial spirit behind the Inklings.

“Scientists/witches like Watho attempt to know nature, but are in error: “human science is but the backward undoing of the tapestry-web of God’s science” (2, 236). MacDonald does not contradict science, nor does he press a theistic interpretation onto his readers. In fact, allegorising too would come close to an “undoing the tapestry” which would be quite alien to MacDonald. Rather he replaces anthropocentric science with an ecological perspective in which nature and its “sympathetic forms” come first, whether religious/fantastic or scientific/rational.”

[This is John Pridmore commenting on MacDonald’s fairy tales.]

The discourse which thus speaks of nature has its own authenticity and autonomy—The theistic and non-theistic accounts of nature are neither incompatible nor is the one to be reduced to the other.” This is not synthesis or dichotomy.

“Instead MacDonald’s art is to present nature in a natural form, that is, in the form of the fairy tale. The cut-up, labelled, specimen means nothing; the flower is everything: “To know a primrose is a higher thing than to know all the botany of it” (Unspoken Sermons)

Tomberg makes an identical point in this chapter concerning the various “truths” of pantheism, gnosticism, theism, and occultism, as well as offering a “re-weaving” of them to save their magic. Man resists these intellectual and spiritual difficulties, because it deprives him of his illusion of power. So what is the answer?

Imagine, dear Unknown Friend, efforts and discoveries in the opposite direction , in the direction of construction or life. Imagine, not an explosion, but rather the blossoming out of a constructive “atomic bomb”. It is not too difficult to imagine, because each little acorn is such a “constructive bomb” and the oak is only the visible results of the slow explosion…Imagine it, and you will have the idea of the great work, or the Tree of Life.

Isn’t it easier to comprehend the vertical play of invisible forces behind our workaday world, asks Tomberg, than to explain the mystery of how “fully explained” living cells stay alive and multiply? These meditations, like those of the Inklings, ultimately spring from the power of the moral imagination to re-integrate those decayed and splintered faculties of man which have occured as a result of his “triumph” over himself and over Nature. This illusory triumph does have a “truth”, but it only possesses it as a shadow or “intimation” of what could have been, and can still be.

Much of the magic today will consist in a re-weaving of what was undone.

Between a prayer, a chant, and a war-song, wherein lies the difference in our war against “that which all too easily is”?

Leave a Reply